On teaching Plato

some notes on thoughtcrime in Texas

Where to start? The US’s slide toward authoritarianism has, it seems, accelerated. The President’s masked secret police is an ill-trained and thin-skinned bunch that must continually reduce its standards and raise its hiring bonuses to find new recruits, but the turbocharging of their funding in last year’s spending bill – over $70 billion for ICE alone, $100 billion more for other immigration and border enforcement efforts – means that they can terrorize a couple of cities at a time in order to create the spectacle of violence that is their main aim.

Authoritarian leaders must continually generate this kind of spectacle, to galvanize their supporters and disorient their enemies, in lieu of any attempt at normal politics that purports to address real problems. Trump is no student of history, but his intuitive grasp of this principle is clear (cf. Venezuela and Greenland). Things seem likely to degrade further given the fecklessness of opposition leaders, the cowardice of members of his own party cowed by his threats, and the readiness of civil society institutions – not least media organizations (CBS News under Bari Weiss is only the most overt example) and universities – to curry favor with the Mafioso-in-Chief.

I admit to feeling a good deal of despair over this latest bundle of events. But, while we can’t easily change the political system or leaders we have, I want to make the case here that our everyday actions can still be a bulwark against and a kind of response to this political nightmare.

I wrote extensively last year about Columbia University’s appeasement of the Trump Administration, with a special focus on its willingness to trade academic freedom for the security of certain income streams. But the collapse in the norms around academic freedom is much more widespread. Even my own current institution Hunter College bowed to political pressure last year and modified a job ad for a Palestinian Studies position after open interference from New York governor Kathy Hochul.

Public institutions in Republican-controlled states, especially those with vanguardist factions in their legislatures such as Texas and Florida, are, however, worse off. My alma mater the University of Texas at Austin has seen significant fights over academic freedom and political interference over the past year, largely stemming from the Trump Administration’s higher education ‘Compact’, which offers special funding in exchange for promoting conservative viewpoints on campus. While the senior vice provost for academic affairs has been dismissed from his administrative post for ‘ideological differences’ – let’s call it what it is: wrongthink – faculty firings and direct interference with classroom teaching have not yet followed at UT.

In that regard, the situation is more dire at Texas A&M University, whose flagship campus dominates my hometown, a place which has long made me wonder: Can anything good come out of College Station? Given the traditional rivalry of the two universities and my own apostasy in going to UT, I would take a sort of satisfaction in this, were it not for the disastrous effects on faculty and students who deserve better.

The latest cycle of trouble began with the firing of an English instructor a few months ago, who was removed for daring to teach a novel with a nonbinary protagonist in a class on children’s literature in the summer. No law or policy banned this material, but once the controversy reached social media and Republican lawmakers and activists got involved, the then-President of A&M demoted the Arts and Sciences Dean and the English department chair over their handling of the underlying event. That didn’t save him from being made to resign himself, apparently for the mistake of defending the right of the instructor, at least in the abstract, to teach such material in the first place (more wrongthink!).

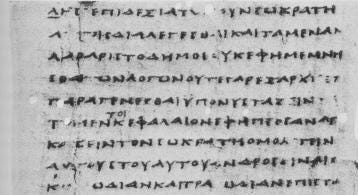

The latest controversy is likewise a bit of gender trouble, but the target is somewhat more sympathetic than ‘woke’ children’s literature, which likely explains the greater national news coverage. An ethics professor at A&M has been told to take Plato’s Symposium off his Spring syllabus because it would violate new university policies against advocating race or gender ideology in the classroom, which were put in place after the earlier episode. This perplexing decision seems likely to invite legal action, not least since there is no evidence whatsoever that the professor in question, who holds a chair in engineering ethics (and is therefore quite a bit more secure than the English lit lecturer was), was planning to advocate any viewpoint in his Contemporary Moral Problems course.

I taught an upper-level seminar on Plato on pleasure and desire this past Fall at Hunter. I chose this topic because Plato’s reflections on pleasure are the most sophisticated that I know in the history of philosophy. Plato is wonderful, and his dialogues are worth reading purely in their own terms. But the intellectual benefits of working through the arguments about pleasure and desire in the Meno, Gorgias, Protagoras, and Philebus are there even if you’re not particularly invested in ancient Greek philosophy. I was convinced of that before the semester started, and my clear sense from talking with my students – and from reading their splendid final papers – was that they came to agree with me.

I didn’t assign the Symposium in that class because it’s a text full of twists and turns, which I thought deserved more time for proper consideration, though it came up regularly in our class conversations. But to make up for this omission, I resolved a couple of months ago to include the Symposium in the course on Philosophy and Literature I will be teaching next Fall along with John Cameron Mitchell’s extremely gay musical film Hedwig and the Angry Inch, which is in direct dialogue with some of the ideas in the Symposium. I now feel even surer of this decision.

The Symposium is about eros or yearning, the kind of desire we feel when we take ourselves to be missing something we can’t live without. The dialogue consists largely of a set of speeches in praise of eros, figured by the speakers as a god or (in Socrates’ speech) a daimōn, an intermediary between gods and human beings. One of the most memorable speeches (and the source material for one of Hedwig’s core songs “The Origin of Love”) is given by Aristophanes, the comic poet who viciously lampooned Socrates and intellectuals like him in his play Clouds. Instead of returning the favor by casting him as a vulgar or buffoonish type, Plato puts in Aristophanes’ mouth a striking and even somewhat tragic myth about human nature in which the gods split human beings in half to keep us in check and yearning names our desire for wholeness, a desire for another person as completing what we once were. While the idea of finding your other half has become an empty romantic trope, Aristophanes’ story – and its explanation of our frequently absurd and desperate behavior in matters of romantic love – still has a certain poignancy.

No doubt the objectionable part of the text to the censors down in Texas is Aristophanes’ defense of the superiority of love between men or perhaps it is simply the idea that yearning is common to all human beings, regardless of their gender or the gender of those they happen to yearn for. But the beauty of the Symposium is that Aristophanes’ story is just one in a series of speeches in which different aspects of yearning are brought to light. For instance, Socrates’ speech, especially the part of it he attributes to a wise seer named Diotima, takes up the question of the proper object of yearning and expands it well beyond romantic or sexual attachment to include all our pursuits of Goodness and Beauty. Despite this point of disagreement, Socrates retains the important idea from Aristophanes’ speech that we yearn because we are fundamentally incomplete and needy creatures.

You can’t teach the Symposium or its arguments about yearning properly without talking about gender and sexuality, in part because sexuality turns out, in the final analysis, to be a sign of something profound about us, something worthy of our intellectual scrutiny just to the extent that Plato has his characters take yearning to be something divine and worthy of praise.

That’s precisely why teaching Plato, and teaching the Symposium in particular, is now a thoughtcrime in the state of Texas. Greg Abbott and his minions want to tell undergraduate students at Texas universities that gender and sexuality are perfectly obvious and that the only reason someone would bring up these topics – except perhaps as part of an abnormal psychology course – is to advocate for what they call ‘gender ideology’, though they’re also not really capable of providing any sort of competent definition of what that is supposed to be. (They have enough shame not to simply say ‘it’s what the woke left thinks’, but the contortions that result show that that’s what they mean.)

Among other errors, there is a profound misunderstanding of the nature of the humanities here, one that, we should acknowledge, is also shared by some left-wing activist academics. The deepest questions the humanities raise for us – like the ones raised by the Symposium: Why do we yearn? Is it part of human nature to be discontent? – are ones that touch on many aspects of life all at once and inquiry into them tends to leave us less settled in the answers with which we began.

You can’t hive off ‘gender and sexuality’ from broader questions about human life and human nature and human experience, as if they could be kept at a safe distance, and you can’t be sure that students (or professors) will keep the views they had when they entered the classroom to talk about them, at least if they are doing so seriously. That means, for example, that students with left-leaning views and right-leaning views alike might have to weigh what difference it would make if sexual orientation turned out to be a choice and not part of our essential nature, as Aristophanes’ myth describes.

Inquiry, when done well, is an intellectually risky business. Plato’s dialogues begin from this conviction, and in relating Socrates’ attempts to get others to think again and so, in fact, to begin the work of really thinking, they challenge our own preconceptions. If I were going to be very daring, I might even call the whole enterprise queer.

Our everyday lives offer us opportunities to push back on creeping authoritarianism. Active and vocal political resistance, to be sure, is needed in these dark times, but reading and thinking seriously are also countercultural activities. Trump and his allies and imitators want us to spend our time outraged, and outrage is antithetical to this kind of intellectual work, simply by crowding it out of our minds.

The case I hope to continue to make to my students – which is really a way to continue to make the same case to myself – is that in pursuing the truth, wherever it lies, we prove ourselves to be unbowed by these political forces and we resist the passivity that is the condition of their success.

Oh, so the authoritarians need ICE violence, blah, blah, blah. You left off the part about Biden letting in over ten million illegals. Of course brutality and racism are the result of that. It is the body politic’s immune system killing the invasive virus. It’s happening all over Europe, too. If you want it to stop quit infecting us next time you get control.